How to Read a Statement of Cash Flows

This is the final topic within the three-part “Financial Statements” section of the Finance 101 for Lawyers series. Previous sections discussed common features of an Income Statement and a Balance Sheet. Last, but not least, let’s cover the Statement of Cash Flows.

Guiding Principles

A Statement of Cash Flows is a financial statement designed to show the sources and uses of cash over a period of time. It is always split into three categories:

- Cash Flow Generated from Operations – How much net cash did the company generate from its day-to-day operations?

- Cash Flow Used in Investing – How much net cash did the company invest in Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E) during the period?

- Cash Flow from Financing – How much net cash did the company raise from issuing new debt and equity, minus what it paid to the debt and equity holders?

At the bottom of the Statement of Cash Flows these three categories are totaled to describe the net impact for the period on the company’s cash balances. This is often compared against the change in the company’s cash balance on its Balance Sheet between the beginning of the period and the end of the period.

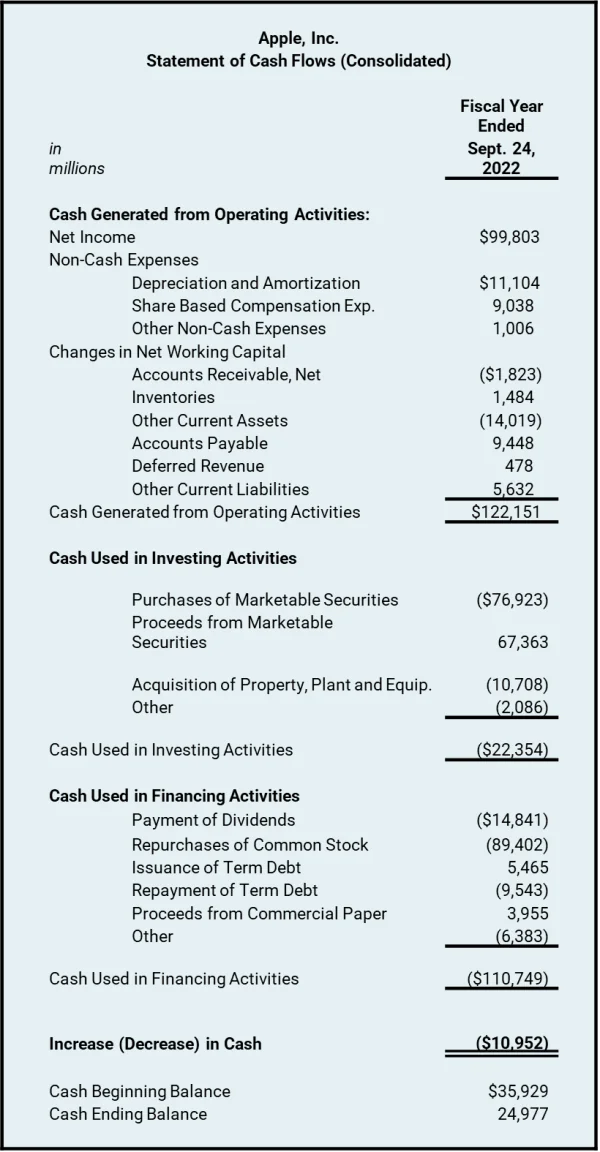

Example: Apple, Inc. Fiscal Year 2022

The Statement of Cash Flows shown here is a simplified version included as part of Apple’s 2022 Annual Report. Apple refers to this statement as a “Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows.” The word consolidated means this statement includes the Cash Flows from Apple’s subsidiaries, not just the parent company Apple, Inc., separately. Also, as part of Apple’s Annual Report, we know this statement complies with the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and is presented on an Accrual Basis. This statement is identified as representing the Fiscal Year ending September 24, 2022, so we know as a reader this statement includes Apple’s performance for a twelve-month period ending on that date.

A Cash Flow Statement always has three distinct categories and a total. The three categories are always presented in the same order: Cash Flow from Operations, Cash Flow from Investing, and Cash Flow from Financing.

Cash Flow from Operations

On Apple’s Cash Flow Statement this category is referred to as “Cash Generated from Operating Activities.” This section is intended to track the sources and uses of cash related to the Operating Activities of the business. The presentation (almost) always starts with Net Income – the earnings of the business. However, since Apple reports on an Accrual Basis, the accounting net income does not match the cash flow. Adjustments to the net income include:

- Non-Cash Expenses – Certain expenses are recognized on the Income Statement, but really do not represent a cash outlay during the period. The most common example is Depreciation. When all of the equipment owned by a company decreases in value every year because it gets older, we say it “depreciates” in value. Depreciation is an expense that gets recorded on the income statement and thereby has lowered the company’s Net Income. However, the company did not hand anyone cash or a check for that expense – Depreciation is a non-cash expense. Therefore, if you are starting with Net Income, you need to add back Depreciation (and other non-cash expenses) to determine the amount of cash generated by the business.

- Changes in Net Working Capital – The company’s Net Working Capital includes parts of the current assets and current liabilities listed on the Balance Sheet. As those account balances change year-to-year, they may result in being a source of extra cash or a use of cash. The net of the changes in Working Capital needs to be added to Net Income as well to get Cash Flow from Operations. Changes in Net Working Capital are best thought about in light of sources and uses of cash. If Accounts Receivable goes up, that is a use of cash (i.e., there is more revenue in the Income Statement than cash collected from customers). Conversely, if Accounts Payable goes up that is a source of cash (i.e., the company is stringing out its vendors and has paid less in cash than the expenses shown on its income statement). Depending on the changes in the various Working Capital accounts, the net impact may either be a source of cash or a use of cash – something to either add or subtract to Net Income.

The Cash Flow from Operations is the cash generated by the normal operations of the business and is the Net Income plus the non-cash expenses plus (or minus) any changes in Net Working Capital.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

This category includes the sources and uses of cash related to the company’s investments in equipment, machinery, and in Apple’s case, marketable securities. As the company buys equipment or securities it uses cash (a negative on the cash flow statement). As the company sells marketable securities it previously bought or sells equipment it previously bought, but might no longer need, it is generating cash (a positive on the cash flow statement).

For a company heavily invested in capital equipment, the Cash Flow from Investing Activities can be significantly negative when there are large outlays. Apple is a bit unusual in that it generates so much cash flow from operations that it chooses to park some of that cash through investing in marketable securities. So, Apple is showing negative cash flow from investing activities, but the net investment in marketable securities is as large as the investment in property, plant, and equipment.

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

This category includes all the ways the company acquires third party funding through various debt and equity instruments. Taking a bank loan is a source of cash and would be a positive number. Paying the principal back on that loan would be a use of cash and be a negative number. Offering new equity shares to the market is a source of cash. Conversely, paying dividends or doing share buy backs are uses of cash. The net impact of all of these different funding sources is the Cash Flow from Financing Activities.

Total and Reconciliation

The end of the Cash Flow Statement will always include the net increase (or decrease) in cash during the period. This is simply the total of the three categories above (Cash Flow from Operations, Cash Flow from Investing, and Cash Flow from Financing). Just be mindful of the positive numbers and the negative numbers – don’t flip a sign inadvertently. In most presentations, a positive number is a net increase in cash and a negative number is a net decrease in cash.

Often at the very bottom of the schedule is a reconciliation section. The total increase (or decrease) in cash listed on the Cash Flow Statement should match the difference in the cash accounts on the Balance Sheet between the prior period and the current period. The cash balances on the Balance Sheet are often listed at the bottom of the Statement of Cash Flows for reference and to confirm that reconciliation.

Summary

A Statement of Cash Flows represents the various sources and uses of cash experienced by the company over a set period of time. The Cash Flow from Operations starts with Net Income and makes the adjustments to determine the cash generated from operating the business. The Cash Flow from Investing is the cash generated by (or used by) the company when investing in things like equipment and marketable securities. The Cash Flow from Financing Activities is the net cash generated (or used) in debt and equity financing operations.

About the Series

Finance 101 for Lawyers is an ongoing educational series of professional insights intended to explain core accounting, finance, and business valuation concepts to lawyers. The series is designed to provide an overview of these topics to assist lawyers as they counsel their clients on financial issues and present financial information to judges and juries.

Note that the discussion represents an overview of certain financial concepts. As with any summary, certain nuances and complications are not addressed in detail. Appropriate financial analysis should consider the specific facts and circumstances of each situation.

About the Author

Brian Dies, CFA, ASA is a Principal at Archway Research and is an expert in the financial analysis of complex transactions, business valuations, and damages in commercial disputes. Mr. Dies holds the Chartered Financial Analyst designation and is also an Accredited Senior Appraiser in the Business Valuation discipline with a specialty designation in Intangible Asset Valuation. Mr. Dies has also spent time as an Instructor at the Harvard University Extension School teaching Business Valuation at the graduate level.